February 1, 2023

10 min read

In August 2020, we were commissioned by a client with a cache of locked QText documents from the mid 90s - to which he has lost the passcode.

QText was a DOS era Hebrew-English word processor written in Turbo Pascal, released 15 or so odd years before neither I nor @Elisha had laid hands on a reverse engineering tool.

In this blog post, we’ll describe the process of analyzing the encrypted documents and reverse engineering a DOS program.

Hopefully we’ll be able to provide some insight into the early days of software development in Israel, and more generally into how cryptography was viewed and implemented in the early days of consumer software development. We also hope to help preserve the knowledge and tools utilized here - a lot of which have scarcely survived to this day.

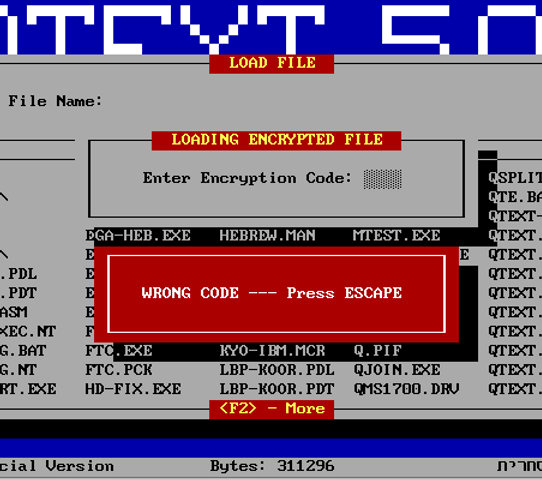

Luckily, we had access to working QText binaries, supplied by our client. We loaded up an instance of the DOSBOX emulator and proceeded to play around with the word processor for a while - focusing on the document encryption feature.

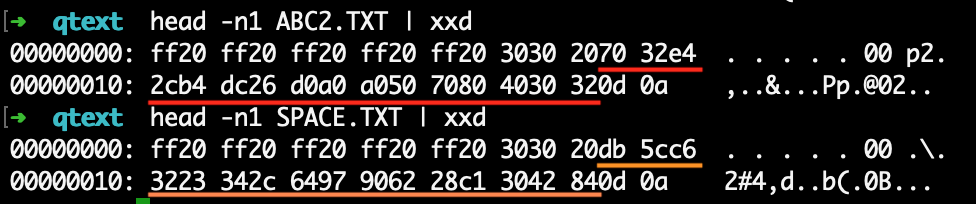

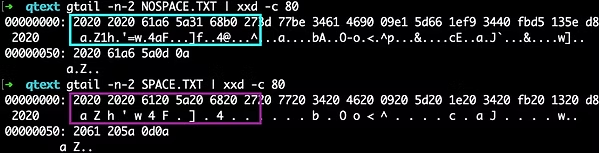

Our initial conclusions included the following:

So a very rudimentary system, as you might expect considering this was developed at a time before the internet was commonplace - let alone knowledge of cryptographic best-practice.

The key seems to be included in the file, but we don’t know the encryption mechanism. We could try and reverse engineer the encryption function, but brute-forcing the passcode is feasible, and in this case much simpler - if we have a fast way to test the passcodes.

Working under the relatively safe assumption that the 16 byte key in the file is somehow derived from the passcode - we can try and focus our RE efforts on the key derivation algorithm. Our first guess was that the passcode was simply hashed using a hash function from that time, but that direction unfortunately didn’t pan out.

We set our sight on the key derivation algorithm and started taking apart the executable.

DOS operates in real mode, meaning the entire 16 bit address space is shared between all processes and is addressed using a 16 bit segment selector and an additional 16 bit address - which are used to cover a usable memory range of 640KB.

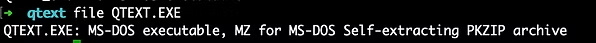

Executables are not PEs, but DOS MZ executables. The file utility recognizes our QTtext binary as a PKZip packed SFX - self extracting executable.

PKWare is responsible for the popularity of the ZIP file format as we know it today, and also for a for a widely used executable packer in the MS-DOS age.

There isn’t a lot of readily available information about the PKZip packer - presumably it utilized the same compression algorithm as the non-SFX zip utility, but we were struggling to find a tool that would properly unpack the SFX to a functioning executable.

Having failed to find additional information about this packer, and wanting to avoid reverse engineering the unpacker stub - we attempted to use the DOSBOX debuggers CPU LOG feature to step past the unpacker code, sometime after the original entry point - and then extract the code from memory.

While this did work, it only accounted for a small part of the code - the executable was 24K in size (packed).

Recalling older days of reversing crackmes (though not as old as this program), we went looking for a generic executable unpacking tool which used to be a dime a dozen on cracking sites.

Preceding some open-source trends by over a decade, their inner-working were often mysterious, but most of the time they did the job. Eventually we found the following ssokolow blog post which guided us to the the a mythical reverse engineering relic - exetools.

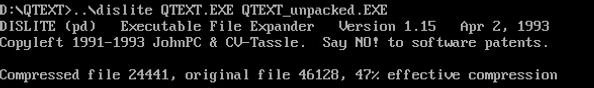

The unpacker page had a huge list of unpackers, we assume a lot of them would have done the job - as PKZip was fairly common. We first tried the one called PKUNLITE, and when that didn’t work (but looked promising) - we found success with DISLITE v1.15.

Loading the binary in IDA Free 5.0 (which luckily is still in distribution - hosted at the ScummVM website) showed that the executable utilized Turbo Pascal like memory overlays.

Since we’re running in real mode, paging/swapping memory wasn’t possible, and overlays were the solution to the limited memory space.

The overlay mechanism was essentially an implementation of page swapping in user-space: The executable contained root segments of non-movable memory, and was accompanied by an .ovr file which contained additional code (in this case, a LOT of additional code).

The root code (which originates from the .exe file) is always mapped into memory, while segments of the overlay were mapped into memory selectively and swapped on-demand.

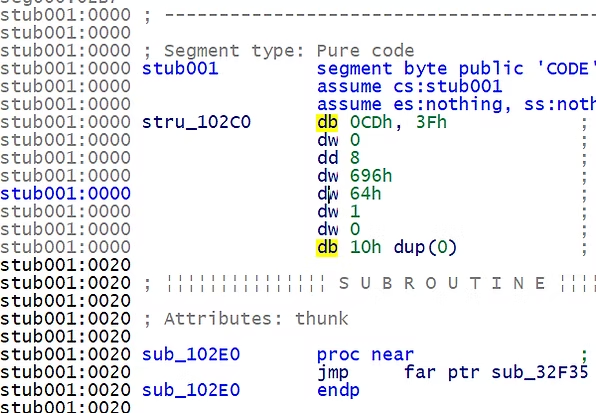

Calls between overlays (and the root segment) occured through a jump table, if the overlay was already mapped into memory, the jump table stubs were “linked” to its current location in memory.

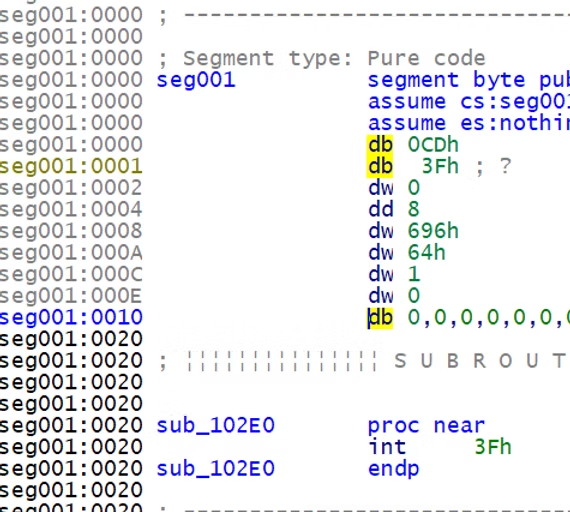

Otherwise, it led to (in this case) an int 3f instruction, and alongside it - the overlay metadata.

The overlay metadata contained - among other things - the file offset of the relevant code segment.

The interrupt handler would then map the relevant overlay into memory, in place of another overlay, and fix up the stubs, before resuming execution.

IDA does an excellent job in flattening and statically linking the stubs so we can reverse engineer the program in its entirety.

However this presented a challenge for us in dynamically debugging the code, since while the root segments were always loaded into the same memory area, the overlays would change location very often, making it impossible for us to place breakpoints properly.

Dredging up information about the Turbo Pascal overlay system was difficult, and the DOSBOX debugger did not conveniently support stepping out of the interrupt.

It’s likely that we could have reverse engineering the interrupt handler and found a place to break in right before resuming program execution in the newly loaded overlay, but we eventually opted for a simpler solution - finding an overlay-to-root call that we could break on and then step out into the newly loaded overlay.

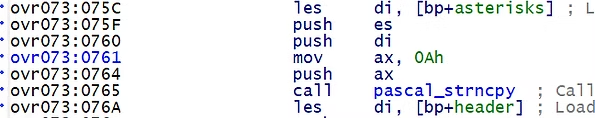

In the above example pascal_strncpy is located in the root segment and its address is fixed and predictable. To break into the calling function in overlay 73, we would instead place a breakpoint at pascal_strncpy and step out into the calling function.

This is slightly arduous but for the fairly short task at hand it would work, and we had ample overlay-to-root calls to break on since the root segment hosted a lot of Turbo Pascal standard functions.

Finding the key expansion function took some reversing and a lot of tracing. Our initial idea was perform hot spot analysis by using DOSBOX’s CPU LOG command to trace execution while repeatedly failing the passcode check on a locked document.

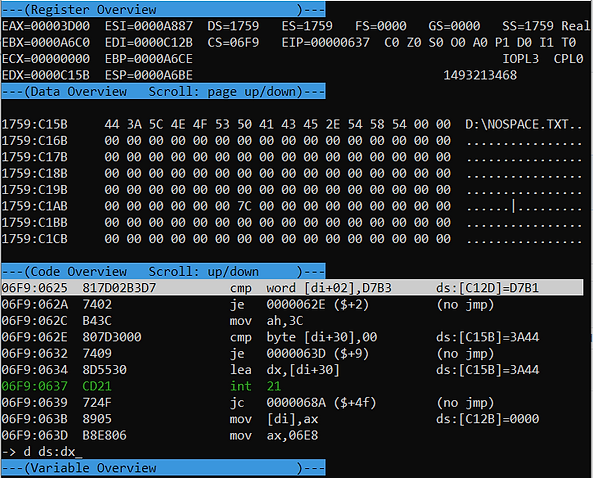

Eventually we went for a more direct approach and simply placed a breakpoint on the int 21 interrupt handler to catch open and read calls.

We traced through an open on the document path and a read of 0𝑥1𝒟 bytes - which is the exact size of the header we saw in locked documents. Continuing with dynamic debugging, we pinpointed a function that takes the entered passcode string and the 0𝑥1𝒟 header as parameters.

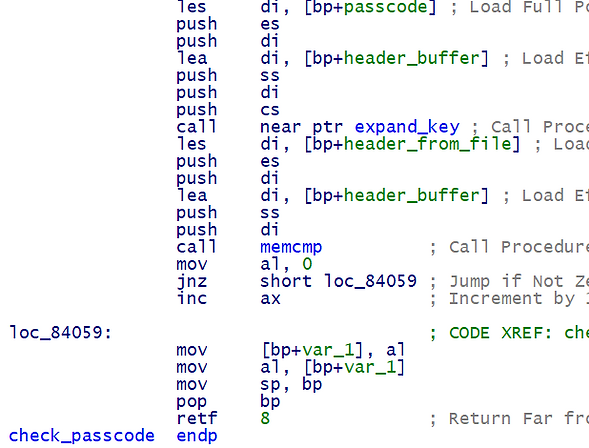

Digging in, we see how the the passcode is passed into an internal function, and the result is compared to the header.

Presumably, the function call prior to the memcmp performs key expansion, and the result is then compared to the file header.

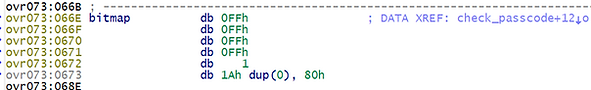

The passcode is first passed through a permutation function which iteratively increments each byte of the passcode by the sum of all bytes in the string. Before proceeding to the byte in the next position, a certain predicate is tested by using the value of the resulting byte as an index into a static bitmap - where each bit represents whether or not that byte value is valid (1) or not (0). A more modern example of this sort of bitmap in use can be found in CFG.

After each byte is permutated, the byte value is tested. If the value is invalid - it is incremented by 0𝑥22. In the case of our immutable bitmap - this “correction” is always enough to push it into the valid value range - meaning it can only occur once per byte.

Excerpt from qtext_cracker.py - the predicate recreated in python

Concretely, this can be represented by simply checking if 0𝑥22 < value < 0𝑥100 🤷

The permutation function 𝑃(𝑥) is simple - it iteratively increments each byte by the sum of the entire string at that point:

Excerpt from qtext_cracker.py - the permutation function recreated in python

After that, the string is concatenated to itself (in place) 3 times, and passed through the permutation function again. The result of this is indeed the key as it appears in the header.

Thus the key derivation function 𝐾(passcode) is:

𝐾(passcode) = 𝑃(𝑃(passcode)|𝑃(passcode)|𝑃(passcode)|𝑃(passcode))

Now we can brute-force the passcode which has a very small input space very quickly. However, with our new-found knowledge of the key derivation function, we can try to reverse it for an even quicker solution.

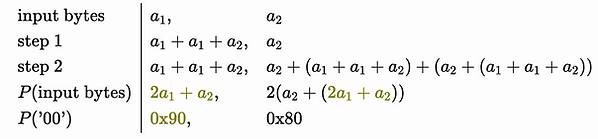

Let’s first examine a simple case - the result of permutating a simple two character string - ‘00’:

The permutation process for a string of length 2 can also be described as:

The permutation only involves combinations of our input values - so it’s linear, but it isn’t strictly linear - we lose the carry bit in any operation that overflows 0𝑥𝐹𝐹

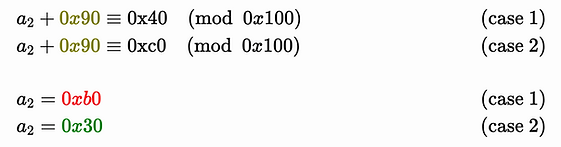

Let’s say we want to reverse the permutation - starting from the last byte. We know that 𝟸𝑎₁+𝑎₂ evaluated to 0x90 so we can substitute for it:

But now, since we have to divide by 2 (which is not invertible in this field) - there are two possible solutions:

We happen to know that the correct value here is 0𝑥30 , but generally speaking when trying to invert the permutation function we’ll have to superimpose both results. Simply put - at each step of the decomposition process, we “split” into two branches - one for each result.

In addition, for a certain range of values, another split occurs - at the end of each byte permutation, if the byte falls into a certain set of values (0𝑥20 < 𝑏 < 0𝑥100) it is incremented by 0𝑥22.

That means that if the byte we’re currently looking at is between 0𝑥20 + 0𝑥22 ≡ 0𝑥24 and 0𝑥100 + 0𝑥22 ≡ 0𝑥22, we need to consider a case where it may have been incremented to that value, and not arrived at naturally.

Thankfully, the correction accounts for the entire span of the “forbidden” values, so it can only occur once - and thus only accounts for one additional branch.

Summarizing - at each stage of the key decomposition we branch out between once and twice. Below is an implementation of the decomposition algorithm using recursion:

48 def recursive_decomposition(input_key, decomposed_part=None, stop_at=4):

49 assert type(input_key) is bytearray

50 key = bytearray(input_key) # copy

51 if decomposed_part is None:

52 decomposed_part = bytearray()

53

54 if len(key) == 0:

55 # Stopping condition

56 return [

57 decomposed_part,

58 ]

59

60 if stop_at is not None:

61 if len(decomposed_part) >= stop_at:

62 return [

63 decomposed_part,

64 ]

65

66 results = []

67 value = key.pop()

68 if not is_valid_char((value - 0x22) % 0x100):

69 # We have an additional case to process

70 new_key = bytearray(key) # copy

71 new_key.append((value - 0x22) % 0x100)

72 # Where to save this?

73 results.extend(recursive_decomposition(new_key, decomposed_part, stop_at))

74

75 value = (value - sum(decomposed_part)) % 0x100

76 # Subtract trailing (decomposed) characters

77 # Compute two candidates

78 candidate_1 = ((value // 2) - sum(key)) % 0x100

79 candidate_2 = (((0x100 + value) // 2) - sum(key)) % 0x100

80 new_decomposed_left = bytearray([candidate_1,]) + decomposed_part

81 new_decomposed_right = bytearray([candidate_2,]) + decomposed_part

82

83 results.extend(recursive_decomposition(key, new_decomposed_left, stop_at))

84 results.extend(recursive_decomposition(key, new_decomposed_right, stop_at))

85

86 return resultsExcerpt from qtext_cracker.py - the decomposition function

Considering a 16 byte key, that means between 2¹⁶ and 2¹⁷ branches, which isn’t too bad, but luckily there are a couple of constraints that help us minimize the search space considerably.

The first constraint is pretty straightforward - any decomposed byte was originally a passcode byte - meaning an uppercase letter or number.

Considering our example from before - it’s clear we could have only chosen the printable value - 0𝑥30.

The second constraint isn’t as trivial, but still pretty simple - the format of the 16 byte key right before the second permutation is a sequence of 4 bytes, repeated 4 times. That means we only have to decompose a 4 byte suffix - and then test that 4 byte suffix by feeding it through the permutation function and checking if the result is the original key.

That narrows our search space down to 2⁵ for each step - or 2⁶ in total. You could realistically break this encryption on a piece of paper if you have the patience!

So - starting from the 16 byte key (𝑘) as extracted from the document:

The qtext cracker script in its entirety can found here.